With hopes of an upturn in the economy running high in all quarters, one indicator in particular is attracting a lot of attention i.e. inflation. Philippe Waechter, Head of Economic Research and Chief Economist at Ostrum Asset Management, looks more closely at this aspect, which can inflame or stimulate all economies worldwide.

PHILIPPE

WARCHTER

Head of Economic Research and Chief Economist at Ostrum Asset Management

INFLATION RATE COURSE IN 2021

After a long phase when inflation trended short of central banks’ targets, are we seeing confirmation of signs that inflation is now firming up?

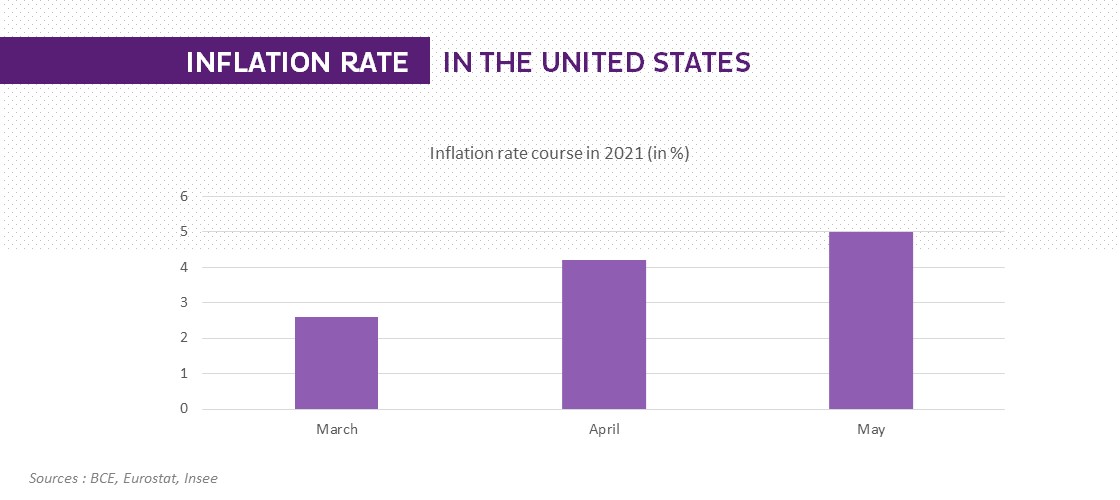

The renewed focus on inflation can be attributed to the situation in the United States, where inflation soared in April and May (see figures above). The surge in May’s figure is the strongest since the Fall of 2008, and far outstrips the Fed’s 2% target.

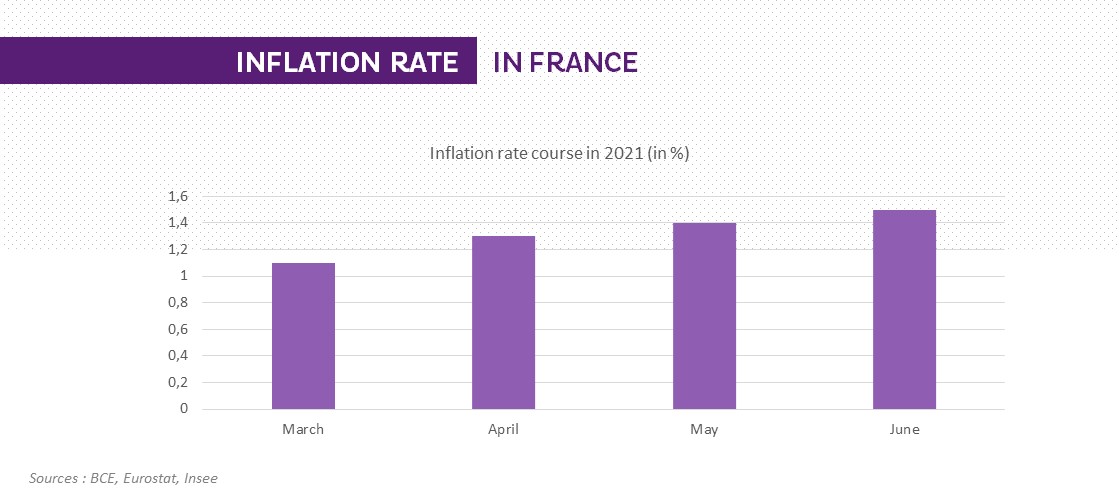

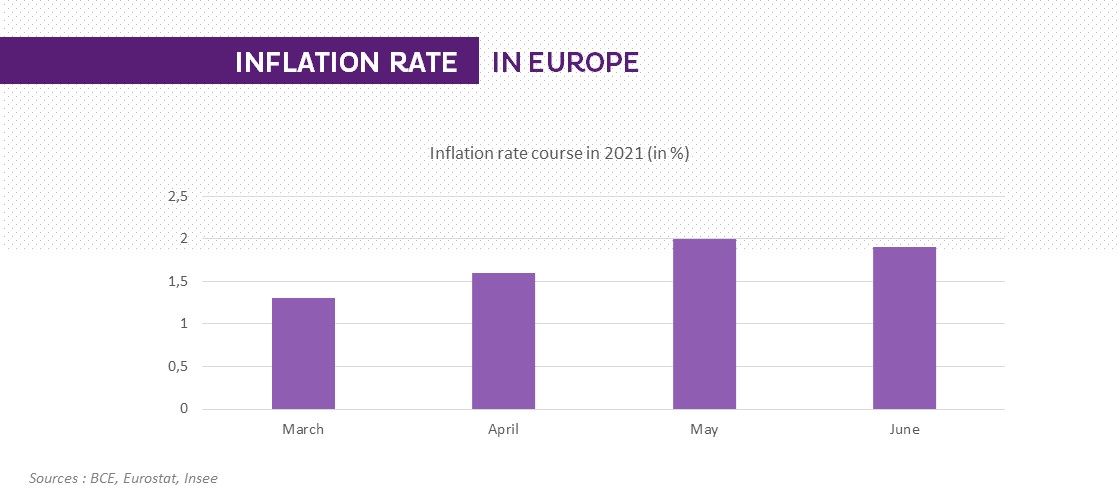

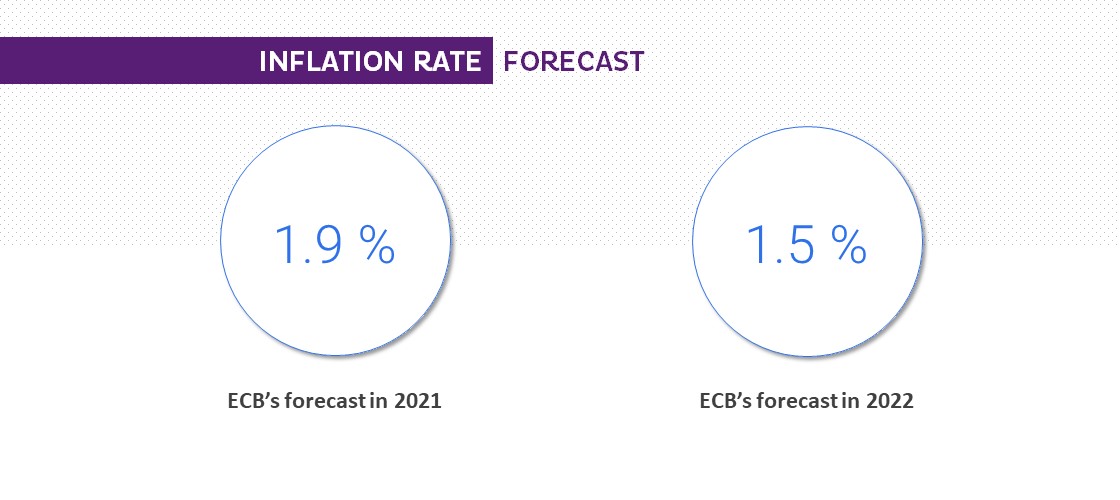

This situation is exclusive to the United States: the euro area is not affected in the same way, with June’s inflation stats slightly short of the ECB’s target.

A first point to bear in mind on inflation in developed countries is the hefty contribution from energy, accounting for 2 percentage points of the 5% inflation figure in the United States in May. Meanwhile in the euro area, 1.2 points of the 1.9% figure in June is down to energy as a result of plummeting oil prices during lockdown a year earlier in Spring 2020.

Looking to the emerging markets, the uptick in inflation is very largely a result of soaring food prices, which account for a very sizeable portion of price indices.

Can the surge in the US be contagious?

The striking aspect of US inflation is the sharp expansion in core inflation – inflation excluding energy and food – which came out at 3.8% in May, hitting its highest point since June 1992.

Looking more closely, we note a very swift gain in transport-related components of the price index. Households were buoyed by the checks paid out under the first Biden stimulus program ($400bn in total in March) and the easing of health restrictions on travel. The price of airline tickets increased, while the contribution from used car sales quadrupled, coming to around 0.8%. With carmakers hampered by the semi-conductor crisis, output was not on a par with required levels, thus prompting consumers to fall back on used vehicles.

US inflation is therefore temporary in nature, due to the effects of both oil and the stimulus program. Meanwhile the pace of price fluctuations is a far cry from this situation in other sectors. Inflation is set to stay at a high clip for several months, so the question now is what impact this will have on wages. If wages are not indexed to inflation, then the pace of inflation will not endure and there will be no reason for the Fed to intervene swiftly.

What is the situation in Europe?

Pressure on prices is much weaker in Europe. Looking beyond energy, which we already mentioned, pressure is slacker. There has been no US-style stimulus program, and households have not enjoyed a sudden windfall. Demand trends are therefore different and momentum is much weaker in the euro area than the United States.

Europe has taken a preventive economic policy approach, curbing risks on jobs and income, while not providing a booster effect. Inflation is therefore not an immediate cause for concern at the ECB.

The point to watch here will be the ECB’s implementation of its new inflation target. The European Central Bank is now willing to accept inflation above 2% without needing to step in, marking a fresh strategy move from the bank as it strikes a compromise between immediate price constraints in the economic cycle and the possible effects of climate change on price formation in the long term. This is a fascinating change as the ECB – aligned with the European Commission – is determined to tackle climate change, thereby bringing a new dimension to the central bank’s role.

How can we project and optimize forthcoming fluctuations?

Central banks do not need to intervene for now, even in the United States. On the one hand inflation is temporary in the US, while on the other hand the pandemic crisis is not necessarily over in the rest of the world. It is too early to rule out these risks and place restrictions on the economy at this point.

The second aspect to monitor will be how wages are indexed to inflation: this was a major driver in persistent inflation in the 1970s.

Thirdly, the economy is changing following on from the pandemic crisis, as countries rebuild. Slightly higher inflation could support this adjustment, similarly to the situation in the 1970s after the first oil shock. A number of sectors in the economy were no longer viable and inflation had facilitated macroeconomic adjustment. A similar mechanism could play out here for the medium term.

Inflation had disappeared from macroeconomic questions and it could return again – although this has not happened yet.